Fashion accounts for around 10% of greenhouse gas emissions from human activity, but there are ways to reduce the impact your wardrobe has on the climate.

“For years I was obsessed with buying clothes,” says Snezhina Piskova. “I would buy 10 pairs of very cheap jeans just for the sake of having more diversity in my wardrobe for a low price, even though I ended up wearing only two or three of them.”

When it comes to resisting the lure of fashion, Piskova faces a tougher challenge than most. As a copywriter for a company in the fashion industry she’s surrounded by fashionistas. And it’s been easy to go along with the tide.

But conversations about the climate crisis made Piskova, who lives in Sofia, Bulgaria, consider the impact that the industry and her own shopping habits were having.

The fashion industry accounts for about 10% of global carbon emissions, and nearly 20% of wastewater. And while the environmental impact of flying is now well known, fashion sucks up more energy than both aviation and shipping combined.

You might also like:

● Should you go on a “flight diet”?

● Why your bin is a climate problem

● The surprising cost of being online

Clothing in general has complex supply chains that makes it difficult to account for all of the emissions that come from producing a pair of trousers or new coat. Then there is how the clothing is transported and disposed of when the consumer no longer wants it anymore.

While most consumer goods suffer from similar issues, what makes the fashion industry particularly problematic is the frenetic pace of change it not only undergoes, but encourages. With each passing season (or microseason), consumers are pushed into buying the latest items to stay on trend.

It’s hard to visualise all of the inputs that go into producing garments, but let’s take denim as an example. The UN estimates that a single pair of jeans requires a kilogram of cotton. And because cotton tends to be grown in dry environments, producing this kilo requires about 7,500–10,000 litres of water. That’s about 10 years’ worth of drinking water for one person.

There are ways to make denim less resource-intensive, but in general, jeans composed of material that is as close to the natural state of cotton as possible use less water and hazardous treatments to produce. This means less bleaching, less sandblasting, and less pre-washing.

The stretchy elastane material in many trendy jeans is made using synthetic materials derived from plastic, which reduces recyclability and increases the environmental impact further

Unfortunately it also means that some of the most popular types of jeans are the hardest on the planet. For instance, fabric dyes pollute water bodies, with devastating effects on aquatic life and drinking water. And the stretchy elastane material woven through many trendy styles of tight jeans is made using synthetic materials derived from plastic, which reduces recyclability and increases the environmental impact further.

Jeans manufacturer Levi Strauss estimates that a pair of its iconic 501 jeans will produce the equivalent of 33.4kg of carbon dioxide equivalent across its entire lifespan – about the same as driving 69 miles in the average US car. Just over a third of those emissions come from the fibre and fabric production, while another 8% is from cutting, sewing and finishing the jeans. Packaging, transport and retail accounts for 16% of the emissions while the remaining 40% is from consumer use – mainly from washing the jeans – and disposal in landfill.

Another study of jeans made in India that contained 2% elastane showed that producing the fibres and denim fabric released 7kg more carbon than those in Levi’s analysis. It suggests that choosing raw denim products will have less impact on the climate.

But it is also possible to look for further ways of reducing the impact of your jeans by looking at the label. Certification programmes like the Better Cotton Initiative and Global Organic Textile Standard can help consumers work out how green their denim is (although these programmes aren’t perfect – many suffer from a lack of funding and the complex supply chains for cotton can make it hard to account where it all comes from).

Some manufacturers are also working on ways to reduce the environmental impact from the production of their jeans, while others have been developing ways of recycling denim or even jeans that will decompose within a few months when composted.

It’s not cotton, but the synthetic polymer polyester that is the most common fabric used in clothing. Globally, “65% of the clothing that we wear is polymer-based”, says Lynn Wilson, an expert on the circular economy, who for her PhD research at the University of Glasgow is focusing on consumer behaviour related to clothing disposal.

Around 70 million barrels of oil a year are used to make polyester fibres in our clothes. From waterproof jackets to delicate scarves, it’s extremely hard to get away from the stuff. Part of this stems from the convenience – polyester is easy to clean and durable. It is also lightweight and inexpensive.

But a shirt made from polyester has double the carbon footprint compared to one made from cotton. A polyester shirt produces the equivalent of 5.5kg of carbon dioxide compared to 2.1kg from a cotton shirt.

Around 70 million barrels of oil a year are used to make polyester fibres in our clothes

Switching to recycled polyester fabric can help to reduce the carbon emissions – recycled polyester releases half to a quarter of the emissions of virgin polyester. But it isn’t a long-term solution, as polyester takes hundreds of years to decompose and can lead to microfibres escaping into the environment.

But natural materials aren’t necessarily sustainable either, if they require huge amounts of water, dye and transport. Organic cotton may be better for the farmworkers who would otherwise be exposed to enormous levels of pesticides, but the pressure on water remains.

However, a great deal of innovation is going into crafting lower-impact fabrics.

Biocouture, or fashion made from more environmentally sustainable materials, is increasingly big business. Some companies are looking to use waste from wood, fruit and other natural materials to create their textiles. Others are trying alternative ways of dyeing their fabrics or searching for materials that biodegrade more easily once thrown away.

But the carbon footprint of our clothing can also be reduced in other ways, too. The way we shop has a big impact.

Some research has suggested that online shopping can have a lower carbon footprint than travelling to traditional shops to buy products, particularly if consumers live far away. But the rise of online shopping has also driven changes in consumer behaviour, contributing to a fast fashion culture where consumers buy more than they need, have it delivered to their door and then return a large proportion of their purchases after trying them on.

Returning items can effectively double the emissions from transporting your goods, and if you factor in failed collections and deliveries, that number can grow further.

It can also be cheaper for internet retailers and fashion brands to dump or burn returned goods, rather than attempting to find another home for them. This not only means the greenhouse gas emissions produced in manufacturing the clothing are wasted, but further emissions are released as it rots or burns. The US Environmental Protection Agency estimates that in 2017 10.2m tonnes of textiles ended up in landfills while another 2.9m tonnes were incinerated. In the UK an estimated 350,000 tonnes of clothes end up in landfill every year.

Piskova periodically swaps clothes with her friends, which not only allows them to refresh their own wardrobes but also helps them feel closer to each other

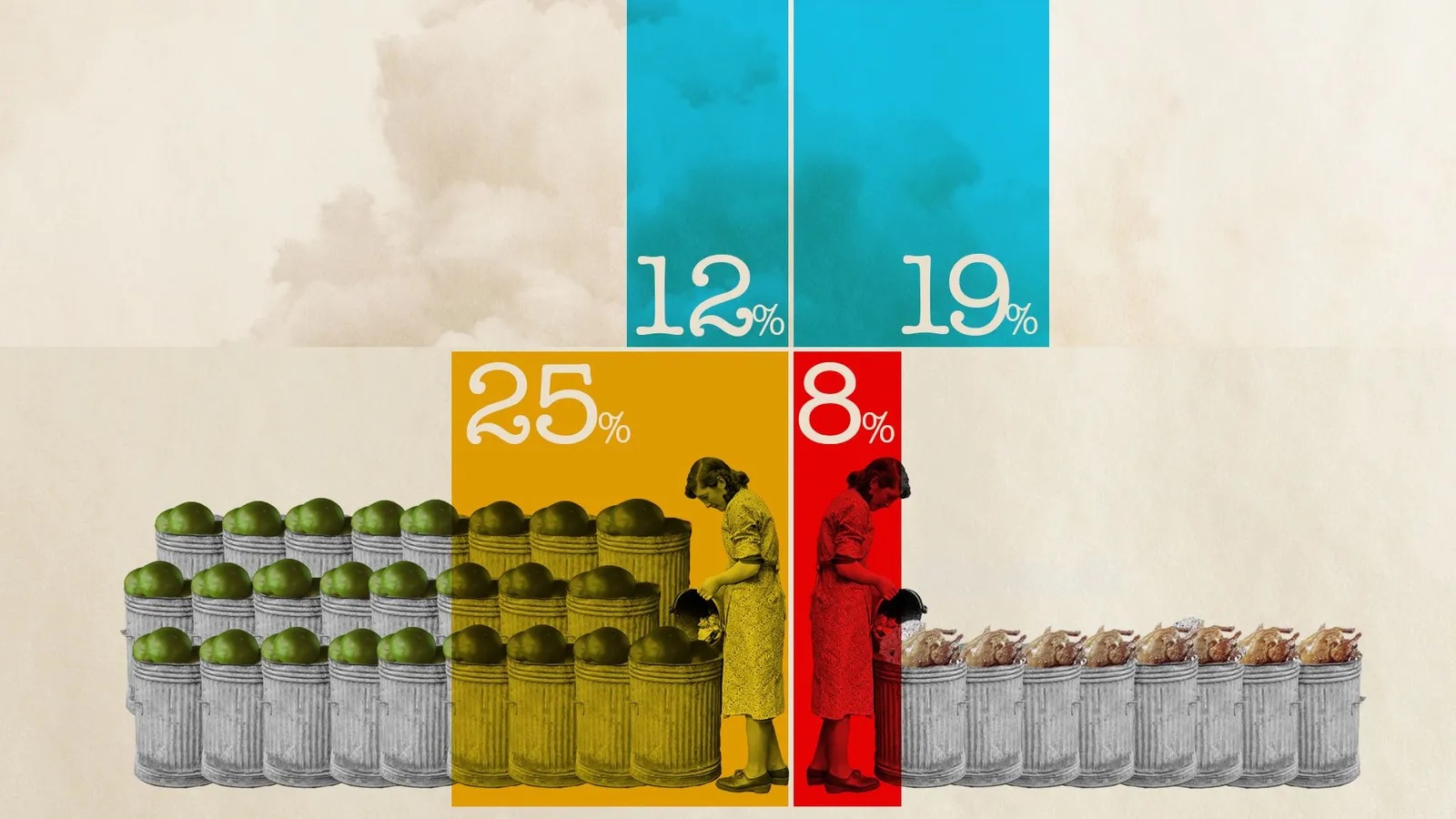

A simple way to reduce the footprint from online shopping then is to only order what we really want and intend to keep. According to the World Bank, 40% of clothing purchased in some countries is never used.

Piskova has tried to move away from the fast fashion culture herself by learning to appreciate what she already has rather than what she could have. But detaching herself from a fashion-obsessed mindset hasn’t been easy. To help, Piskova resists going to places where she feels pressure to consume, such as shopping malls. She also periodically swaps clothes with her friends, which not only allows them to refresh their own wardrobes but also helps them feel closer to each other. And she has also learned to embrace small blemishes on her clothes, rather than seeing these as an excuse to buy more.

“People are so careful with their clothes, like to not have any scratches on them or have any holes or whatever,” says Piskova. “But then when you think about it, that’s part of the clothes. You remember that one time when you went to a festival, where you ripped your shirt or something like that, and it’s a nice memory.”

The number of times you wear an item of clothing can make a big difference too in its overall carbon footprint. Research by scientists at the Chalmers Institute of Technology in Gothenburg, Sweden, found that an average cotton t-shirt might release just over 2kg of carbon dioxide equivalent into the atmosphere while a polyester dress would release the equivalent of nearly 17kg of carbon dioxide.

They estimated, however, that the average t-shirt in Sweden is worn around 22 times in a year, while the average dress is worn just 10 times. This would mean the amount of carbon released per wear is many times higher for the dress.

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the average number of times a piece of clothing is worn decreased by 36% between 2000 and 2015. In the same period, clothing production doubled. These gains came at the expense of the quality and longevity of the garments.

A number of public surveys also suggest that many of us have clothes in our wardrobes that we hardly ever wear. According to one survey, nearly half of the clothes in the average UK person’s wardrobe are never worn, primarily because they no longer fit or have gone out of style. Another found that a fifth of the items owned by US consumers are unworn.

It is clear that investing in higher-quality clothing, wearing them more often and holding onto them for longer, is the not-so-secret weapon for combatting the carbon footprint from your garments. In the UK, continuing to actively wear a garment for just nine months longer could diminish its environmental impacts by 20–30%.

Naturally, some clothing companies have sniffed out an opportunity here. Clothing rental services, for instance, are especially appealing in a social-media era where some people are reluctant to be seen online wearing the same outfit more than once. For those who want to look good in their online photos but have even less of an impact on the environment, there is the ephemeral trend for digital fashion, or clothing designed to only appear online by being superimposed onto your images.

The average t-shirt in Sweden is worn around 22 times in a year, while the average dress is worn just 10 times

Buying less also means caring for clothes more. Websites like Love Your Clothes, set up by UK recycling charity WRAP, offer tips on repairing and extending the life of clothes, which can reduce the carbon footprint of the clothes.

But tackling the underlying reasons for why we over-purchase, yet underuse, clothes could also help. In a consumerist society, people are trained to find fast fashion pleasurable and addictive.

“A lot of the things that we purchase fulfil some kind of function in ourselves – particularly fashion items,” says Mike Kyrios, a clinical psychologist who researches mental disorders at Australia’s Flinders University. People who have lower self-esteem or worry about their status are especially likely to use overspending as a route to feel like they “belong”, he explains. As are people who are sensitive to rewards – indeed the reward centres in the brain are those most activated by impulse shopping.

Online shopping also means that the impulse to buy is harder to control, as internet stores are open 24/7 – including, as Kyrios says, the times “when your decision-making capabilities are at their minimum”.

Though estimates vary, one is that about 5% of the population exhibits compulsive buying behaviour. “The problem is it’s well hidden,” says Kyrios. “People don’t show up for treatment, people don’t acknowledge it’s a problem.”

One solution might be to simply ration the time you spend looking at clothes online, but perhaps a better approach is to find less wasteful ways of achieving the sense of reward that over-spenders are seeking. Mainstream consumers can scratch their itch for new clothes by buying from vintage and secondhand clothing shops.

“Secondhand clothing is giving clothes a second life and it’s slowing down that fast-fashion cycle,” says Fee Gilfeather, a sustainable fashion expert at charity Oxfam. “So I would say secondhand (clothing) is actually one of the solutions to the overconsumption challenge.”

Cutting down on washing can also help to further reduce the carbon footprint of your wardrobe, while also helping to lower water use and the number of microfibres shed in the washing machine.

“You don’t need to wash clothes as often as you might think,” says Gilfeather. She hangs some of her dresses out to air, for example, rather than washing them after each wear. “Reducing the amount of washing that you need to do is the best way of making sure that the plastics don’t get into the water system.”

Throwing clothes away so they end up in landfill or being incinerated simply leads to more emissions

How you dispose of the clothes at the end of their useful life is also important. Throwing them away so they end up in landfill or being incinerated simply leads to more emissions. Perhaps the best approach is to pass them on to friends or take them to charity shops if they are still good enough to be worn. However, individuals should be careful not to use this as a way of clearing space simply to buy new clothes, which Wilson’s research suggests is common.

Where clothing has been worn or damaged beyond repair, the most environmentally sound way of disposing them is to send them for recycling. Clothing recycling is still relatively new for many fabrics but increasingly cotton and polyester clothing can now be turned into new clothes or other items. Some major manufacturers have now started using recycled fabrics, but it is often hard for consumers to find places to take their old clothes.

Many of the changes needed to make clothing more sustainable have to be implemented by the manufacturers and big companies that control the fashion industry. But as consumers the changes we all make in our behaviour not only add up, but can drive change in the industry, too.

According to Gilfeather, we can all make a difference by being more thoughtful as consumers.

Why your banking habits matter for the climate

It might not be the most obvious way of reducing your carbon footprint, but how you save, invest and give away your money can make a difference to the climate.

What immediately comes to mind when thinking about the impact you have on the climate? Is it the flights you take? Or journeys in your car? Or perhaps the food you eat?

What about your money?

The links between your personal finances and the climate emergency are perhaps less intuitive than these other examples. The cash in your bank account, pension, and personal investments may not seem to be a direct cause of greenhouse gas emissions. But the financial institutions you invest with and give your business to could be having a big impact on the environment. As a consumer with money to invest, the decisions you take about what to do with it can be surprisingly important.

For most people, banks are the places that most frequently deal with their money. But many banks are also well-documented financiers of the climate crisis.

You might also be interested in:

- The law that could make climate change illegal

- Is there such a thing as a good or bad recession?

- The simple system that could end plastic pollution

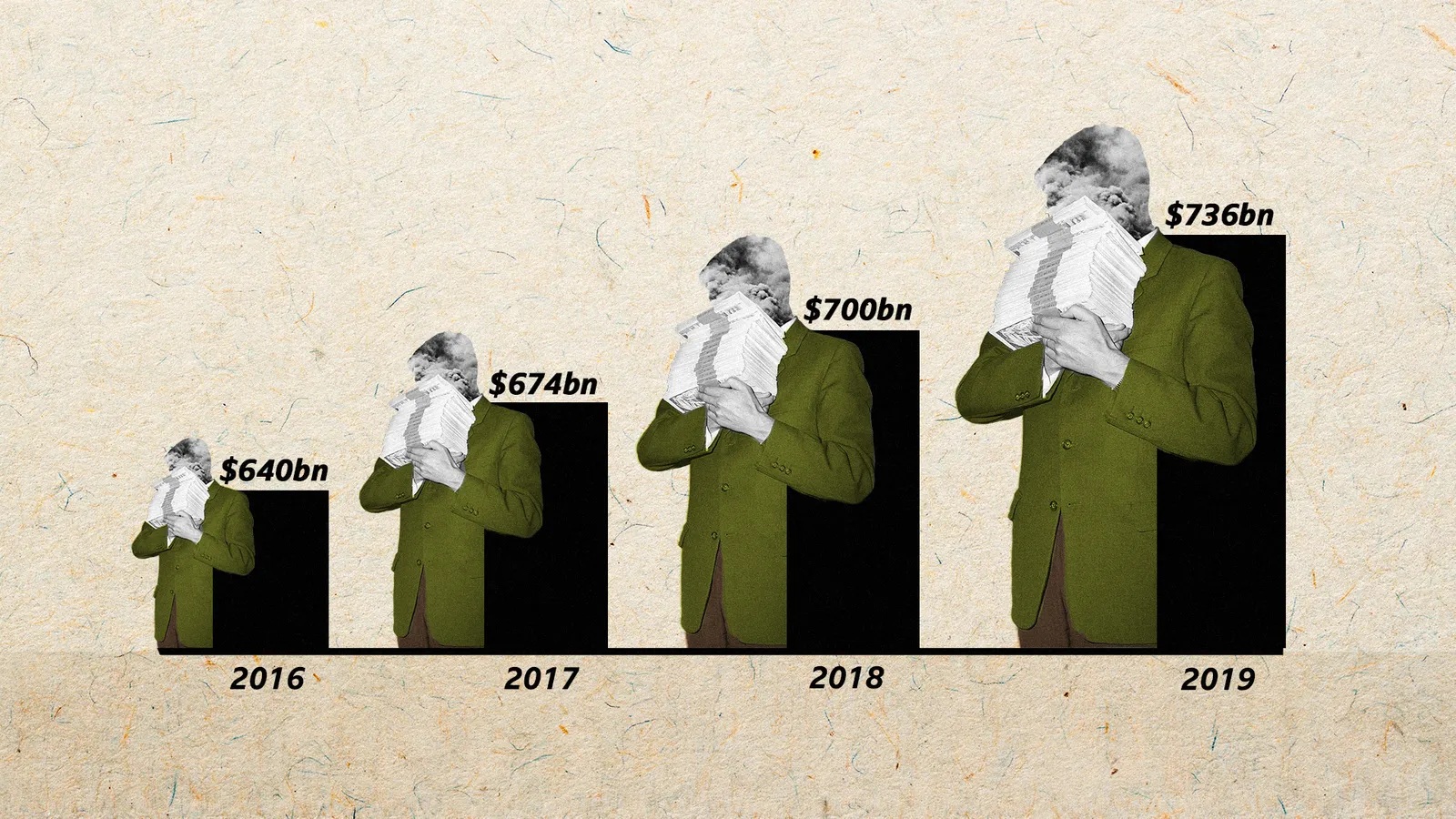

Between them, 35 of the world’s major banks – many of them household names – have provided $2.7 trillion (£2tn) to fossil fuel companies since the Paris Agreement on climate change was adopted at the end of 2015, according to a 2020 report from Rainforest Action Network and five other non-profits. They found this fossil fuel financing had actually grown each year since the Paris agreement.

Many of these banks also offer current and savings accounts to ordinary customers, although this does not typically mean your money is being used for fossil fuel investments. This is because, in most countries, consumer banking arms of banks are separated from their investment arms. The money sitting in your bank account is instead normally used for loans to other customers, such as mortgages, rather than investments.

“Retail banks are ringfenced by law from investment banking,” says Alex Money, director of the Innovative Infrastructure Investment programme at the University of Oxford’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment. “This basically means, from a bank’s point of view, they can’t use money that customers are giving them on deposit to then speculate or take market positions with that money.”

But this does not mean that you as an individual customer are powerless to influence the investment behaviour of your chosen bank, says Louise Rouse, a capital markets campaigner and consultant to various non-profits.

“Banking institutions want to maintain retail bank divisions, that’s important to them,” she says. “It’s also how they build brand identity, it’s how they build social licence, which gives them political power and so on. So, individuals indicating that a bank’s climate performance is an important factor for them in their choice of bank will have an impact.”

A good place to start is to research your bank’s policies.

You have the ability to say to them that you would prefer that they didn’t fund climate change in the way that they’re doing – Louise Rouse

The Rainforest Action Network report names the top funders of fossil fuels and assesses many banks’ climate policies. The non-profit BankTrack, which co-authored this report, also has detailed information on many banks on its website, including lists of which banks exclude financing for Arctic oil and gas companies or for tar sands, where thick bitumen is extracted before being converted into fossil fuels and associated products.

There are a number of high-profile campaigns attempting to put pressure on banks to change their investment strategies. Over the past year, several banks have begun to make some, albeit still insufficient, moves on climate, says Rouse, with increasing customer awareness about the links between these banks and climate change “no doubt” an influencing factor.

As larger groups, customers can exert more influence over the institutions they bank with. “I would encourage a broader consumer frame, rather than just ‘how is my money fuelling the problem?'” says Rouse. “Because you’ve chosen to bank with who you have, you actually have the ability to say to them that you would prefer that they didn’t fund climate change in the way that they’re doing.”

Another approach is to influence the bank from within. Groups such as ShareAction, a charity that promotes responsible investment, have been coordinating shareholders at major banks to file resolutions aimed at phasing out investments in fossil fuel energy companies.

For those who lack the financial power to invest in banking shares, however, you could also consider moving to a different bank if you are unhappy with your current bank’s policies.

“People tend to vote with their feet really about some of these things if they feel strongly enough about it,” says Money.

There are an increasing number of new, small banks marketing themselves as ethical and funders of solutions. Alternatives to banks, such as credit unions or building societies, are also often less likely to be funding fossil fuels due to the way they invest. Non-profit website Ethical Consumer outlines two key things to consider when choosing an ethical savings account: clarity and transparency about how the bank will invest your money, and whether it is a “mutual” – i.e. owned by depositors rather than shareholders.

Another important way of using the power of your money to benefit the planet is through your pension. An estimated $47tn (£34tn) are invested in the world’s pensions, according to the Thinking Ahead Institute’s latest Global Pension Assets Study, and accounts for roughly half of all the money invested in the global financial system.

Less than 1% of assets in the world’s largest 100 pension funds were invested in low-carbon solutions in 2018

“The weight of our pensions within the global economy and the financial system is enormous,” says Michael Kind, campaigns manager at ShareAction. “The biggest and the most important players really are big pension funds.”

However, most people tend to know very little about their pension and typically leave their money in default funds likely to be at least partially invested in fossil fuels. “We’ve found that most people don’t even know their pension is invested,” says Kind. “And where they do know that their pension is invested, they assume it’s invested sensibly and well.”

In reality, less than 1% of assets in the world’s largest 100 pension funds were invested in low-carbon solutions in 2018, according ShareAction’s research. Just 15% had a policy to exclude fossil fuels in some way from their investments and 65% had no formal climate policy at all.

Engaging with your pension and how the money in it is invested can have a big impact, especially if others do the same. “Our pensions are like a huge structural lever within the world economy,” says Kind. “Collectively, if we all took action, [the shift] would be enormous. Individually, one at a time, less so.”

But checking where your pension fund is currently invested is not always easy. This information is not always openly available and you may need to ask for it, although pension providers sometimes provide a “fun fact” sheet online listing the top 10 investments for each fund. This lack of transparency may be slowly shifting – in the UK, for example, pension funds are set to be forced by law to disclose their climate risks.

Often, there is an option to switch personal pensions into an ethical fund, which typically screens out some fossil fuel companies. The top holdings in many of these are Facebook and Amazon, notes Kind.

The cost of being in an ethical fund can also be slightly higher than the default fund, due to the extra research and due diligence needed to establish which companies are ethical, in which case we also need to ask ourselves whether we feel these extra fees involved are worth it.

“There’s a kind of overarching point, which is: what’s the point in saving for a pension if you’re not going to have a planet to retire on?” says Kind.

It’s also worth noting that some ethical pension funds hold onto shares in certain companies in order to engage in “stewardship” – actively using ownership of a company to improve its practices.

Interest in sustainable investment is rising fast – a record $20.6bn (£15.1bn) was put into sustainable funds in the US in 2019

“When considering whether a pension is ethical or not, it’s helpful to look at both the companies it invests in but what it’s also doing with the investments that it has,” says Kind. “You have a lot of power as someone who owns a company to change the way that company works.”

In some cases, your money may be in a defined benefit scheme, which gives you less control to switch to an ethical fund. In this case, ShareAction encourages people to speak to their employer about any concerns that their money may be being invested irresponsibly.

Employers themselves have the power to select a different provider or work with the pension provider to build new funds, says Kind. “That’s really powerful because it’s not just you switching your money then, it’s your entire workplace, which is potentially hundreds of people.”

Caroline Hopper, a copywriter and previously a campaign adviser at the Make My Money Matter pension campaign, became concerned about her own pension investments after reading a report about responsible investing at work. After some digging around in her pension, she discovered its top 10 holdings were in FTSE 100 companies, including British American Tobacco, Royal Dutch Shell and BP. “They’re things that I didn’t want to be investing in,” she says.

She initially switched to the ethical fund offered by the same pension provider, but began finding that many of her colleagues at work were also concerned. In response, her employer decided to offer a more diverse option.

“They got a financial advisor in to set up what’s effectively a personal pension for each one of us, but our employer still contributes into it,” says Hopper. “Some people used the chance to consolidate other pensions, but a lot of us ended up with what we now consider to be much more sustainable funds, which are also performing much better.”

Investing in solutions

For people with these more flexible pensions, or looking to invest money themselves in another way, a whole world of sustainable finance opens up.

Interest in sustainable investment is rising fast – a record $20.6bn (£15.1bn) was put into sustainable funds in the US in 2019, nearly four times as much as the previous 2018 record, according to data provider Morningstar.

Beside the ethics of avoiding contributing to climate change, there is also an increasing awareness of climate risk – the threats posed to some investments both by the physical impacts of climate change and by future policies to tackle emissions. Even BlackRock, the world’s largest money manager in charge of an enormous $7tn (£5tn) in assets, is recognising this now: its chairman Larry Fink last year wrote to clients warning about climate risk and outlining plans “place sustainability at the centre” of its investment approach.

Impact investments, which specifically aim to have a positive impact on the world, are also on the rise. Intermediary platforms such as Nutmeg and Hargreaves Lansdown allow small-scale investors to align their money with their own priorities, while sites like Ethex and Tickr specifically channel investments into companies trying to make a positive difference.

Green donations

Charities are responsible for a huge amount of investment. The 86,000 charitable foundations in the US hold around $870bn (£640bn) in combined assets, and while a small percentage of this is spent each year, much of it remains invested on Wall Street. If you are donating to charity, could your donation end up being invested somewhere you don’t want it to be?

A host of institutions across the world have now committed to divest from fossil fuels. It may be worth checking if the recipient of your donation is one of them and, if not, if it is taking action on climate in another way, such as stewardship.

It’s probably wise to let the bank, university or other institution know about your concerns or the reason you are switching

Another consideration, especially if donating to a university, is what your money will be used for. “If people are making donations to universities, which, for example, are undertaking loads of research for fossil fuel companies, they may decide they wish to give their money elsewhere, or to earmark their donations for departments which are researching solutions to climate change,” says Rouse.

It may also help to find out if the institution also accepts money from fossil fuel companies in case that influences where you choose to donate.

In all these situations, it’s probably wise to let the bank, university or other institution know about your concerns or the reason you are switching.

Who knows – it may just help to shift their gauge a little more towards climate action too.

* Jocelyn Timperley is a freelance climate change reporter. You can find her on Twitter @jloistf.

How your fridge is heating up the planet

The way you dispose of old kitchen appliances and air conditioning units can have a huge impact on the climate.

Whether you are a farmer in Kenya transporting milk to the local market, the owner of a London cornershop or a patient undergoing chemotherapy in Japan, we all rely on devices that keep us, and the things we consume, cool. Without fridges our food would quickly go off, milk would rapidly sour and food poisonings would likely skyrocket.

In the coming months, refrigeration is likely to play a vital role in the current pandemic too. As vaccines begin to roll out, they will need enormous cold-storage supply chains for them to be manufactured, distributed and stored until they are administered. Many other life-saving medications – from insulin to antibiotics – also need to be stored in this “cold-chain” to prevent them from degrading and becoming useless.

In schools, offices, shops and homes in many parts of the world, refrigerants also play an important role in the air conditioning systems that keep these buildings comfortable.

The cooling industry is important, but it is also incredibly polluting – accounting for around 10% of global CO2 emissions. That is three times the amount produced by aviation and shipping combined. And as temperatures around the world continue to rise due to climate change, the demand for cooling will increase too.

With countries and companies under pressure to slash their contribution to climate change, the cooling industry is facing a radical overhaul to the way it produces and disposes of refrigerants. Over the past three decades, governments around the world have pledged to crack down on the potent climate-warming chemicals used as coolants, while companies have started seeking natural, less polluting alternatives. But environmental campaigners say changes must be made much faster if international climate goals are to be met.

Consumers too can play their part through the devices they buy, how they use them and what they do with refrigerant-filled equipment once finished with them.

But what is it about refrigerants that makes them so bad for the climate?

Refrigerators and air conditioning units certainly use a fair bit of energy, especially when they are running continuously in hot climates. But they also contain chemicals that readily absorb heat from the environment as they turn from being a cool liquid into a gas. As they transition back to liquid, they release the heat into the outside – either outside a building or outside a fridge – before being cycled back to begin the cooling process again.

These same chemicals are also used in some types of insulation foam and as the propellant in aerosol spray cans.

Their capacity to warm the atmosphere is thousands of times greater than carbon dioxide, with some being up to 11,700 times more potent

The most common type of refrigerant used to be chlorofluorocarbons, more widely known by their acronym CFCs. But after CFCs were found to be depleting the ozone layer, there was a worldwide effort to phased them out. The 1987 Montreal Protocol – a landmark environmental agreement signed by over 200 countries – means these environmentally harmful chemicals are no longer produced.

But the effort to get rid of CFCs resulted in many chemical manufacturers choosing to replace them with two groups of chemicals with a different problem – hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs). These refrigerants break down ozone molecules far less, but are extremely potent greenhouse gases. Their capacity to warm the atmosphere – measured as global warming potential – is thousands of times greater than carbon dioxide, with some being up to 13,850 times more potent. This is because HFCs and HCFCs – along with CFCs – also absorb infrared radiation, trapping heat inside the atmosphere rather than allowing it to escape back into space, creating a greenhouse effect that warms the planet.

Although these chemicals are used for a number of different purposes, by far the largest source of emissions is from refrigeration and air conditioning systems. Over time they can leak out into the atmosphere from damaged appliances or from car air conditioning systems, for example.

“The industry as a whole has had a huge impact on global warming,” says Clare Perry, senior campaigner at the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a non-profit that investigates and campaigns against environmental abuse. She says taken together CFCs, HFCs and HCFCs have accounted for close to 11% of total warming emissions to date.

In 2016, officials from over 150 countries signed the Kigali Amendment, agreeing to reduce HFC consumption by 80% by 2047. If achieved, this could avoid more than 0.4C of global warming by the end of the century – a sizeable amount in our efforts to reduce the effects of climate change.

As HFCs are potent gases that can remain in the atmosphere for up to 29 years, there is an urgent need to phase them out, says Doug Parr, chief climate scientist at Greenpeace. “Once they are produced, they are problematic to deal with. You’re building a problem bank of chemicals,” says Parr.

But industry experts say these harmful refrigerants are still widespread and increasing rapidly due to a global surge in demand for air conditioning, sluggish innovation from industry and inadequate legislation around their disposal. All around the world, the demand for air conditioning is growing as temperatures rise and people become wealthier, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Recent heatwaves in Europe have also driven sales of air conditioning in areas where they were previously uncommon.

The number of global cooling devices is estimated to increase from 3.6 billion to 9.5 billion by 2050, according to a report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the IEA. Providing cooling to everyone who needs it, and not just those who can afford it, will require 14 billion devices by 2050, the report notes.

You might also like:

- The food that could last 2,000 years

- How to stay cool without air conditioning

- The smart way to stay warm this winter

“As countries in the global south are starting to increase their wealth, their ability to purchase air conditioners and refrigerators is increasing dramatically,” says Brian Dean, head of energy efficiency and cooling at the UN-backed initiative Sustainable Energy for All.

Without radical changes to the cooling industry, HFC emissions are projected to contribute warming equivalent to 20% of CO2 output in 2050, the UNEP report warns.

Roughly 90% of refrigerant emissions occur at equipment’s end of life

There are ways to cool a home without the need for air conditioning. Traditional approaches use water features such as fountains to help cool the air passing through a building, while others use careful design to encourage natural air circulation. Even simple approaches like placing an earthenware pot of water near a window or drafty spot can help to cool a room by a few of degrees. (Read more about how to cool your home without AC.)

Part of the problem with refrigerants, however, is that much of the harm they cause is after we as consumers have finished using them. It occurs out of sight, and so largely out of mind.

Roughly 90% of refrigerant emissions occur at equipment’s end of life, according to Project Drawdown, a nonprofit that analyses climate solutions. This means that proper disposal is essential. If the refrigerant chemicals are carefully extracted and stored, they can be purified for reuse or turned into other substances that do not cause global warming.

Proper management and reuse of potent refrigerant gases could slash 100 billion gigatons of global CO2 emissions between 2020 and 2050, according to the EIA. But proper disposal of HFCs is not a mandatory requirement under the Montreal Protocol and is not properly enforced in many countries, according to UNEP.

The most common HFC found in domestic fridges is HFC-134a, which has a global warming potential 3,400 times that of carbon dioxide. A typical fridge can contain between 0.05kg and 0.25kg of refrigerant, which if it leaks into the environment, the resulting emissions would be equivalent to driving 675km-3,427km (420-2,130 miles) in an average family-sized car.

Consumers looking to get rid of their old fridge, freezer or air conditioning unit in a responsible fashion have a number of options open to them. In the US, old appliances can be disposed of through schemes approved by the Environmental Protection Agency. Many local authorities will pick up and recycle old appliances, while manufacturers and retailers of new devices often offer to take away the old item. Efforts to phase out HFCs in the US have been added to the recent energy innovation bill that is currently going through the Senate.

In the European Union, legislation already requires HFC gases to be recovered at end of life to prevent them from leaking into the atmosphere. If your fridge breaks in the UK, for example, you are required to take it to a licensed waste facility where a technician removes the gas. It is illegal to not reclaim the refrigerants before destroying an appliance.

But a recent study found that global emissions of HFC-23, which has the highest global warming potential of all HFCs, reached an all-time high in 2018 despite international efforts to reduce it. HFC-23 is a byproduct in the production of HFCF-22, which is a common propellant and refrigerant used in air conditioning units. The rise suggests that not enough is being done to collect and destroy HFC-23 during manufacturing processes.

In many countries there are no proper regulations in place. This is especially a concern in developing countries, according to Dean.

“If [people] decide to keep [their appliances] and maybe smash them in the backyard, there’s no regulatory mechanism that stops individuals from not disposing of refrigerants properly,” he says.

In some cases HFCs are also finding their way into products illegally, which is threatening to undermine efforts to phase them out. Following new regulations introduced by the European Union in 2014, prices of HFCs have soared. But the EIA claims there are discrepancies in export and import data of HFCs leaving China and arriving in the EU. In the second half of 2019, 54 tonnes of HFCs were seized, a ten-fold increase compared to the same period in 2018, according to unpublished analysis by EIA.

According to Perry, ineffective enforcement is allowing large-scale illegal HFC trade and some of these may end up in devices sold to consumers. “Probably the highest risk for your average consumer is that illegal HFCs could be used to service the air-conditioning in your car, she says. “So it’s worth asking your service garage how they ensure that the HFCs they use are from a reputable source.”

Manufacturers have started turning to climate-friendly chemicals, known as natural refrigerants, which have comparatively low or zero global warming potentia

The chemical industry is taking steps to stop illegal trade in HFCs and consumers can find out which companies have pledged to take action on a website they set up. But more needs to be done, says Perry.

“If the illegal trade continues apace it will threaten the integrity of the HFC phase-down and EU climate targets,” she says.

For those already looking to replace their fridge or air conditioning unit with something that is better for the planet, there are a growing number of options available. Manufacturers have started turning to climate-friendly chemicals, known as natural refrigerants, which have comparatively low or zero global warming potential.

Major global brands such as Coca Cola, PepsiCo and Unilever have set goals to phase out HFCs and already started using alternatives. Ammonia, certain hydrocarbons and CO2 are the most popular options.

Coca Cola has pledged that all new cold drinks equipment it uses will be HFC-free and has already switched to using the hydrocarbon propane in many of its vending machines. Unilever ice cream brands, including Ben & Jerry’s and Wall’s, also use hydrocarbons in their freezers.

Most supermarkets in Europe now use CO2 in their fridges and freezers after EU regulations to phase out HFCs were introduced in 2015.

But safety concerns are hindering an industry-wide transition towards natural refrigerants. Ammonia, for example, is highly toxic meaning it would present a health risk should it escape through a leak while propane is a flammable gas. But relatively small amounts of these chemicals are needed in the sealed tubes that circulate them around fridges and air conditioning units.

Environmental campaigners say chemical manufacturers are also resisting the shift to these natural substances.

“They cannot patent CO2, hydrocarbons or ammonia because they are natural substances,” said Marc Chasserot, who founded Shecco, a market accelerator for natural refrigerants. “They will tell you that they are dangerous, [but] no Coca Cola vending machine using hydrocarbons has ever blown up. The flammability risk can be managed very easily,” he claims.

US chemical manufacturer Honeywell has invested in hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) instead of natural refrigerants, producing a patented chemical called HFO1234yf. “In many applications, these solutions have a global warming potential that is equal to, or better than, carbon dioxide and as much as 99% lower than other HFC technologies,” says George Koutsaftes, Honeywell’s president of advanced materials.

But Perry says these substances are not long-term solutions as they produce toxic acid as they break down in the atmosphere which pollutes groundwater. “Natural refrigerants are the only [ones] that are basically future proof,” says Perry. “The phase out is going to continue and only be strengthened, [making potent refrigerants] more and more rare and expensive, and eventually illegal.”

Some countries have already introduced labelling to help people easily identify which fridges contain these more climate-friendly alternatives

One company that has committed to phasing out HFCs is Mabe, a major Mexican manufacturer that distributes appliances to over 70 countries. It has announced that it will completely phase out HFCs from its 11 production plants this year, replacing them with hydrocarbons.

“We want the world to know that the transition to new refrigeration alternatives is possible,” explains Pablo Moreno, Mabe’s head of corporate affairs. He claims the move could reduce the company’s CO2 emissions by 240,000 tonnes per year. Another manufacturer, Electrolux, has pledged to remove all HFCs from its fridges and freezers by 2023.

For consumers, however, working out which appliances contain natural refrigerants is not always easy. Some countries have already introduced labelling to help people easily identify which fridges contain these more climate-friendly alternatives.

But with so many HFCs sitting in kitchens and air conditioning systems around the world already, our desire to stay cool could make the world a lot hotter.

* An earlier version of this article incorrectly implied that CFCs were not also potent global warming gases. This has been corrected. It has also been corrected to clarify the source of HFC-23 as a byproduct of HFCF-22 production.

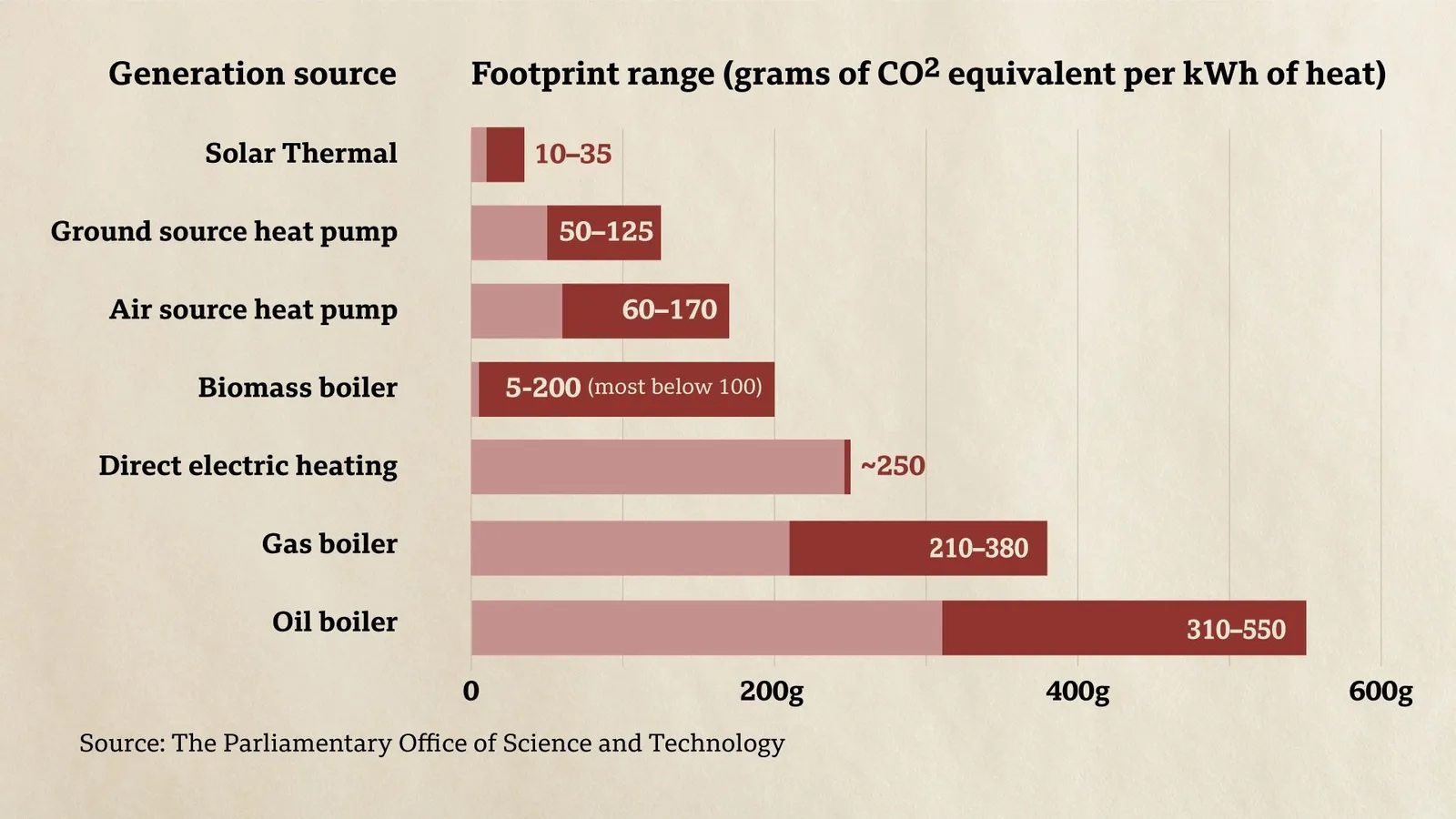

How to cut carbon out of your heating

With many people spending more time than usual in their homes this year, how can the environmental cost of heating them be reduced?

When it comes to heating, retiree Lucy Craig’s bungalow in north London is high tech. A self-professed gadget lover, when she refurbished eight years ago, she was keen to find the most carbon friendly methods for keeping her home warm. She settled on heat pumps.

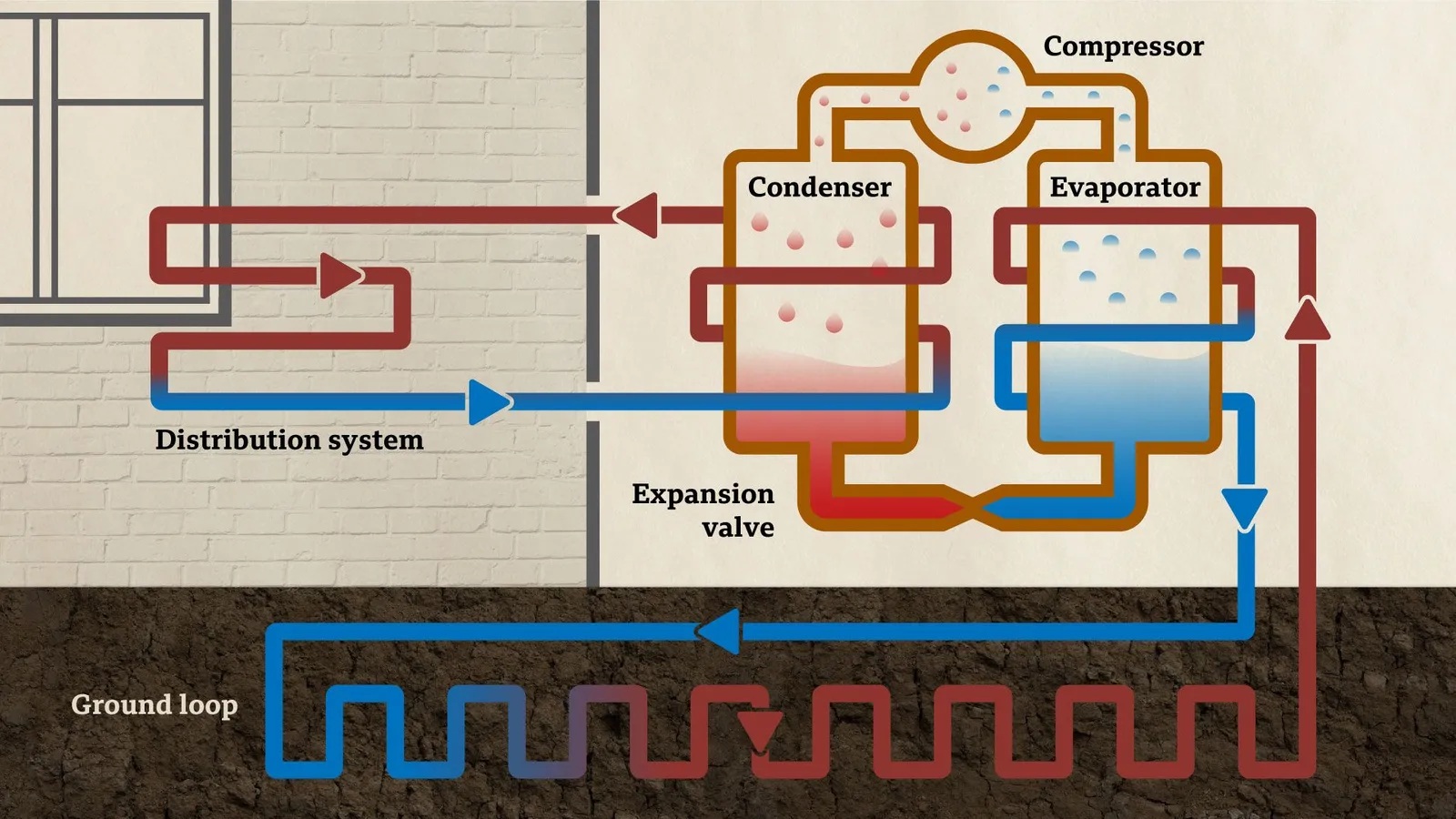

Outside her house, all that can be seen of the pump is an innocuous metal box. Inside the machine is a closed circuit of liquid that cycles in a pipe running from the box outdoors to a water tank indoors. This liquid is a refrigerant with a very low boiling temperature, so even winter air has enough energy to vaporise it. At the outdoor box, the heat pump fans air over the refrigerant, helping it to absorb heat, which it then transfers to the water tank inside the house.

Craig has one of these pumps to generate hot water for an underfloor heating system and another that generates hot water that runs from the taps. On her countertop, an owl-shaped monitor on the tells her how much she is using. It’s usually good news. Heat pumps use only around a quarter of the energy needed for a traditional gas boiler and Craig is able to get the electricity needed to keep the system running from solar panels she has had installed on her roof.

What makes heat pumps so efficient is the refrigerant gas inside the network of pipes. It flows through a cycle of evaporation and condensation as it absorbs heat from the air, turns to vapour and is then compressed with an electric-powered pump. This compression step helps to concentrate the energy stored in the refrigerant. When it gets inside, the refrigerant cools and condenses as it transfers its heat to the water in the inside tank.

Even in low outside temperatures, it can generate enough heat to keep Craig’s home warm and produce enough hot water for her needs. It is a highly efficient process, and is leading many to see heat pumps as the future of home heating.

The energy used to heat the spaces we live and work in is one of the highest contributors to our individual carbon footprints. Globally, heat accounts for nearly half of all energy consumption and 40% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. Of course, exactly how much of your own emissions come from heating your home will depend on where you live. In cooler and temperate climates, that tends to be a far bigger proportion.

In the US, 38% of greenhouse gas emissions from residential housing are produced from heating and cooling rooms, while a further 15% are produced heating water. It is estimated that 19% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions come from warming up the places we live and work, with more than three-quarters of this coming from domestic buildings. The vast majority of houses in the UK rely on gas boilers, but the British Government has moved to phase these out in the next five years.

You might also like:

- Why eating your leftovers helps the planet

- The hidden cost of your daily water use

- Why your house could be a gold mine

There are plenty of less carbon intensive alternatives for householders to switch to, such as using electric heating, heat pumps, or even district heat networks, where a central source is used to heat water, which is then shared among nearby houses through networks of pipes.

The carbon footprint of heating, however, is only one half of the story. In order to cut down on emissions quickly, as well as prepare for low energy alternatives, “our houses need to be warmer”, says Hannah Jones, a mechanical engineer at a UK-based green design consultancy called Greengauge. “If we all just add heat pumps to most houses as they are we’ll need more energy than they can provide.”

This means we need to be able to trap what heat we get into our homes inside rather than allowing it to leak out.

This challenge motivated Craig to participate in Muswell Hill Sustainability group, a network of carbon-friendly homeowners in north London who are trying to demonstrate how carbon savings can be made. Through the network’s thermal imaging group – “the TIGgers” – homeowners can have their property photographed using heat-sensitive cameras to reveal where they are wasting the most energy.

“People are often surprised to see their roofs are bright red with heat loss,” says Craig. “It’s one way to motivate communities to decarbonise the country’s housing stock en-masse.“

Once you have found where the heat is leaking out, it is then possible to do something about it.

Where to start

New builds are easier to tackle. Installing cavity insulation and new double-glazing during the construction stage saves replacement costs in the future.

For the majority of the people, however, the challenge is how to adapting their existing properties. Much of the housing in Europe and North America is more than 40 years old. In the US 13.5% of homes were built before 1940 while a third of the housing in the UK, Denmark and Belgium were constructed prior to 1946. In Germany, Hungary and Sweden 45-50% of the houses were built between 1946 and 1980 while in Italy, Slovakia and Romania the share of housing of that age rises to 50-60%.

Despite this, huge carbon savings can still be made by retrofitting the existing housing stock, according to Jones. Making sure doors shut properly is a good first step, and that they are draught proofed, with no gaps. “Door brushes, beading and rubber seals alldo their bit,” she says. “Not everyone can afford new cavity wall insulation, but everyone can drought-proof their letterbox.”

According to a report from the University of Sussex, new double-glazing (manufactured after 2002) provides one of the most significant carbon savings. If all houses got new double-glazing it could save the UK 20.3 TWh of fuel per year. Assuming the heat saved is generated from natural gas, the savings would amount to 3.76 million tonnes of CO2 per year – around 1.2% of the nation’s total annual carbon emissions.

In a house with five radiators, reflectors could save £20 ($26) a year from energy bills

For households that can’t afford to refit windows, there are also magnetised versions available, where a second pane can be stuck over the top superficially. They fit different size and types of window, and come at about one-fifth of the cost.

Making the best of a boiler

While the energy you use to heat your home makes a big difference to the carbon footprint, there are other ways of reducing emissions.

Terence Jeffrey is a green energy consultant, based in Islington, London, where he advises residents how to get more heat out of their existing boiler systems. He recommends people pay attention to their radiators.

“We always recommend radiator reflectors” he says. “Much of radiator heat is lost through the mounting wall, a reflector it bounces back 95% of it.” In a house with five radiators, reflectors could save £20 ($26) a year from energy bills, he estimates.

More efficient still is to turn off radiators that aren’t being used. Thermostatic radiator valves can be added and used to control the heat in individual rooms. “Letting the other rooms be a little cooler is going to save carbon,” Jeffrey says. Internet connected “smart” valves allow even greater control.

Turning down room temperature down by 1C can have a big cumulative effect. According to Element Energy, the UK would save 1.18 million tonnes of CO2 if everyone carried out such a decrease. Jeffrey is quick to add, however, that many of his clients are in fuel poverty, so dropping the temperature further is not always an option for those already scrimping by on the barely any heat anyway.

He does recommend lowering the running boiler temperature to 60C. “A lower temperature over a longer period is better than firing it up to higher temperatures in short bursts” he says.

Insulation and passive designs

After draught proofing, insulation is the most important way to cut back on carbon.

At its most extreme is a rigorous sustainability energy certification called “passive house”. The movement has its roots in 1970s American architecture, when the energy crisis meant homes were designed to maximise as much as possible on insulation and “solar gains” – the free heat that comes from the sun.

“It was a case of necessity becoming the mother of invention,” says Julie Torres Moskovitz, who completed the first certified passive house in New York. Growing up in the 70s, she remembers colouring-in exercises about how to save energy during the crisis at school. “Energy has always been a theme for me,” she says.

To achieve passive house level of energy efficiency, a home must use below 15 kilowatt hours per square meter for heat for the whole year annually – about a 10% of that used by the average home.

A dog might give off 50 watts while an oven, a refrigerator and electric lights also add to the warmth inside the building

“Virtually airtight” is how Moskovitz describes the requirements of a passive house. “If the standard for insulation are met, a passive house can reduce heating energy consumption of its occupants by up to 90%,” she says.

A passive house needs a high level of insulation, and to eke as much use as possible from the heat available inside. External insulation on the outside of the building is one of the most effective at creating a sealed envelope and avoid “thermal bridges”, which wick heat from warm indoors to cold outdoors. But it can also be the most expensive and, thanks to its change of appearance, runs up against planning permission problems.

There are easier and cheaper options – 10mm-thick insulation can be rolled on like wallpaper to internal walls. “Adding a layer roof insulation is also very easy to do,” says Jones. “A roll of mineral wool to the floor of cold loft space could make a noticeable difference.”

Insulation doesn’t just trap heat from radiators – it also keeps in warmth produced by other sources too. “Each person in the house is going to be giving off 100 watts,” says Justin Bere, a sustainable architect in London. In a 100sq m (1,076 sq ft) three bedroom passive house, it should only require 1kW to heat the building even in the coldest months, he estimates. “So in a family of five you’ve already got half the warmth you need for the house.”

A dog might give off another 50 watts while appliances such as an oven, a refrigerator and electric lights also add to the warmth inside the building.

Bere’s point is that if the house can be fitted to hold onto the warmth inside, there is less need for more from carbon-emitting sources.

While many new builds are being fitted to passive house standards, existing buildings can also be retrofitted with insulation. Bere often uses insulation panels that are as thick as a mattress and are attached to wooden board. These can be drilled on the interior of existing walls. “It means the rooms come in by 10cm (4in) on every side,” he says. “However, most people barely notice the difference in the end, and the added comfort is far more valuable than a few centimetres of wall.”

Jones cautions that making a building too airtight can cause problems when it comes to ventilation. “You really don’t want to encourage mould growth, or create poor air quality,” she says. Installing a mechanical vent that circulates fresh air, while recovering the heat can help here.

Accidental emissions

While adding insulation and other measures to make your home more energy efficient might seem to make sense, there is a risk that the carbon footprint of the construction materials themselves could cancel out any savings made.

“It can sometimes be a zero sum game,” says Ahmed Khan, a professor of sustainable architecture in Belgium.

Through research at the Université Libre de Bruxelles, he found some of the most energy-efficient products, such as brand new insulation materials and triple glazing, can be more carbon heavy over their lifetime due to the energy needed to manufacture and transport the materials. This is called embodied energy.

Rather than fibreglass insulation, cellulose fibres, mineral wool from mineral waste, cork and even wasted blue jean fabric can be used

There is a sweet spot though. “It’s possible to achieve a very high energy efficiency and low embodied energy, so long as you pay attention to the sources of materials,” says André Stephan, expert in energy efficiency at the Univerité Catholique de Louvain.

Favouring materials that come from natural sources, repurposed waste or reused materials can help. “It truly depends on the location of your home, but as a general rule materials which are bio-based and not fired at very high temperatures are typically less energy intensive,” says Stephan. Less energy intensive means less greenhouse gas emissions.

Rather than fibreglass insulation, cellulose fibres, mineral wool from mineral waste, cork and even wasted blue jean fabric can be used. “Reaching passive house standards or equivalent with these materials is ideal for a low carbon footprint across the life cycle of the property,” says Stephan.

Smart heating

In the remains of a coal mine in east Belgium is a laboratory which is experimenting on another potential solution for keeping carbon emissions down. This is the EnergyVille complex where Chris Caerts researches “smart” fixes to improve energy efficiency. He’s often asked, is intelligent technology the answer to emitting less carbon?

“Compared to having a boiler switched on all the time, a remote app which turns it off when it is not needed will appear revolutionary,” he says. “But a well-programmed ‘dumb’ thermostat could achieve near the same savings.”

“We need systems that work automatically and learn how to make the most of changeable energy such as wind and solar.” That might mean a hot water system that activates when it receives a strong signal from the solar panels, or even knows when to expect one.

In theory, an intelligent heating system should be able to make similar decisions on a daily basis, with information from regional wind and solar farms. Consumption could be timed when there is the greenest energy mix forecast.

For those with gas boilers, a smart thermostat which learns which rooms you use and when could also help to reduce your carbon footprint some, says Caerts.

While truly intelligent, flexible systems that adapt to the energy mix might still be some years away, a change in mentality can start now. The National Grid, for example, launched an app earlier this year which allows users to work out when the greenest time to use electricity is. One website even offered those taking up baking during the pandemic lockdown to decide the best time to crank up their ovens in order to have the least environmental impact.

“We need to be thinking about how we can steer consumption to maximally coincide with times in the day when the carbon intensity is the lowest,” adds Caerts.

With many of us likely to be spending more time in our homes this winter, it could make a big difference.

The hidden impact of your daily water use

The way we do our laundry, clean our dishes and hose down our cars all has a surprising and largely unnoticed impact on the climate.

Jackie Lambert suspects that her habit of showering only every three days is unusual. “But I’m unapologetic for it because I think it’s fine,” she laughs. After all, a daily shower is more about cultural expectations than hygiene.

To be fair, Lambert’s whole lifestyle is on the unusual side. After she and her husband were made redundant in their early 50s, they decided to rent out their house in the coastal town of Bournemouth, UK, and move into a caravan with their four dogs for much of the year. At the moment, they’re in a village in the Italian Alps.

“The limit when you’re caravanning is the fact that you very rarely have water hooked up to the caravan,” explains Lambert, who worked in sales before she retired. “You have to collect all the water yourself.”

The couple typically fill 40-litre water carriers at caravan sites, and roll them along the ground to their caravan. “It’s surprising how quickly you get through that,” says Lambert. “So, certainly, the lifestyle does make you very conscious of how much water you use.”

You might also like:

● Why we need to walk more

● Why your bin is a climate problem

● The surprising cost of being online

A good example is laundry. The couple use a portable twin tub washing machine, an electricity-powered device with two compartments that requires a bit more manual input than a typical modern washing machine. First, they pour warm water into the left side, which runs up to 12 minutes on an agitating cycle. They then move the clothes to the right-hand tub – a spin dryer. “We re-use rinse water for the next wash if it is clean enough to do so,” explains Lambert. Though small, the gizmo can even accommodate duvet covers.

This kind of machine may be impractical for most homes. But domestic laundry has a surprisingly large carbon footprint. The power needed to run household appliances, and especially the energy required to heat up water, has a carbon footprint that’s largely invisible to householders. Yet all of our water use adds up. It accounts for 6% of all carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the UK, while laundry alone accounts for 8% of all residential-sector CO2 emissions in the US. The energy needed to move, treat, and use water in the US for both residential and commercial purposes produces nearly 290 million metric tonnes of CO2 annually – the equivalent of 5% of the nation’s overall carbon emissions.

For a standard new-build home in the UK, the energy used by utility companies to treat and pump water to domestic property is responsible for only about 10% of water-related CO2 emissions. The bulk of the emissions from household water use, comes from the energy needed to heat water in the home, about 46% if a gas boiler is used. About 17% of the emissions come from using dishwashers, and 11% from washing machines. In the US, about 19% of all energy delivered to households is used for heating water, while doing the laundry in each household in the country is estimated to release an average of 240kg of greenhouse gas emissions a year.

Rather than large white-goods, the kitchen sink is actually the source of the most water-related carbon emissions in the home

“Hot water is one of the bigger energy-consuming issues in a household,” says Elizabeth Shove, a sociologist at Lancaster University who researches everyday energy use. While using solar enegy to heat water can make a big dent in that, it is has high installation costs and is far from being available for everyone. Most modern homes tend to use one of two systems to heat their water – either a gas or an electric boiler.

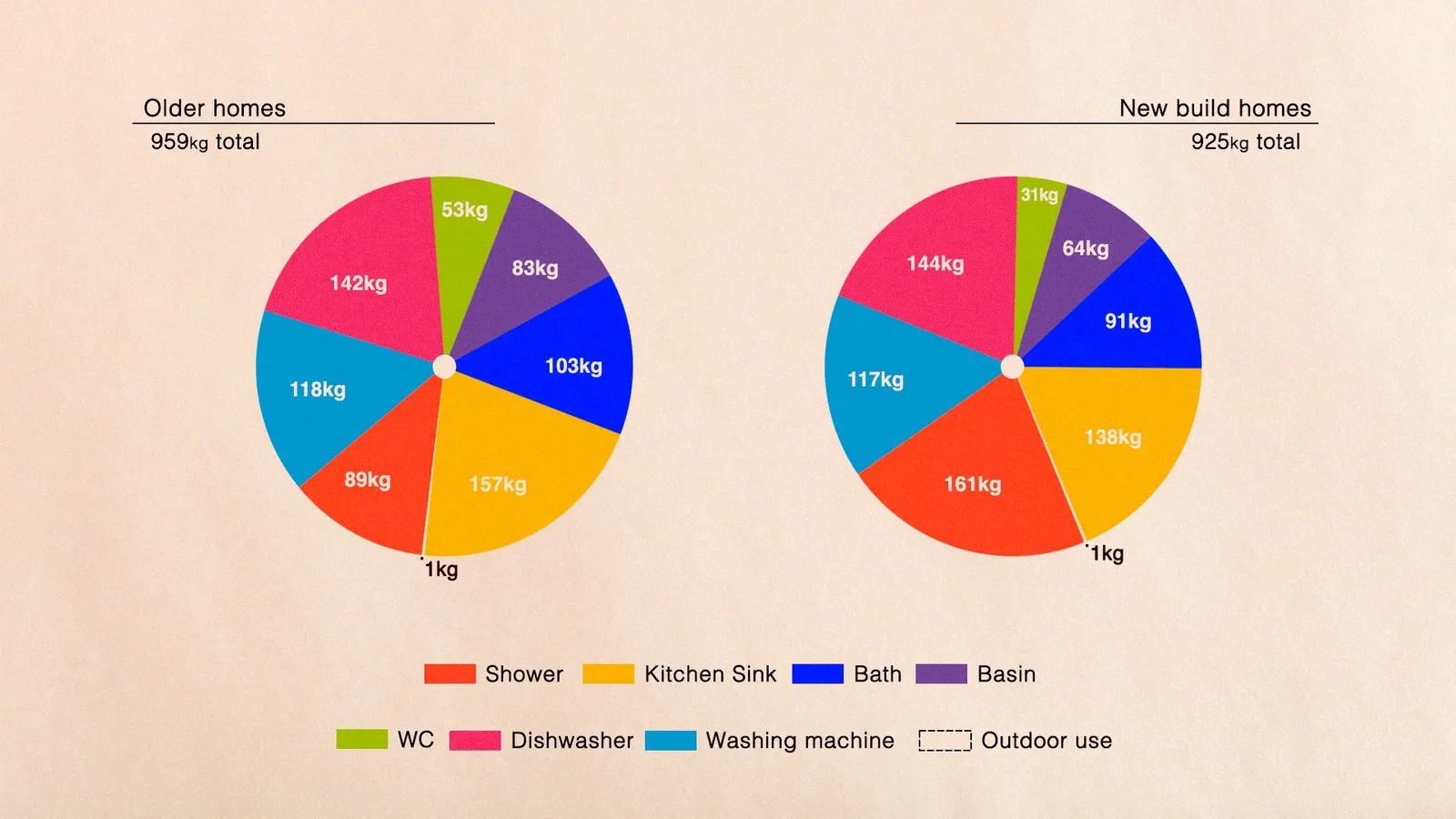

In the majority of houses with a gas boiler in the UK, the main cause of emissions might surprise many households. Rather than large white-goods, the kitchen sink is actually the source of the most water-related carbon emissions in the home. Keeping the kitchen tap running leads to approximately 157kg of CO2 being released per year while the dishwasher produces 142kg of CO2, the washing machine generates 118kg and the bath creates 103kg. (In a newer home, however, the shower is the water-use device with the highest emissions.)

While these figures date from 2009, they are thought to be a reliable indicator of the kind of emissions that come from different water-intensive activities in the home. But there are ways of reducing that footprint.

Surprisingly, using a dishwashing machine more can help. One analysis in the US found that putting dirty crockery and utensils into a dishwasher uses less energy and less water than doing them by hand. It estimated that using a dishwasher could reduce greenhouse gas emissions from washing up by 72% compared to doing them by hand. Pre-rinsing dishes, as many people do under a running tap, can reduce these savings considerably, as can running a dishwasher that is only half full.

But for those who don’t have dishwashers, it is still possible to keep your emissions to a minimum. Being sparing with the water and using less hot water can all make a difference. Using a bowl for washing up, rather than a running tap, could save about 666kg of CO2 a year, according to one analysis – roughly the same as a return-trip flight between London and Oslo.

“We just have a plastic bowl that we would normally fill with an inch or two of water, and do the washing up in that, and rinse in clean water,” says Lambert. “We try to use as little water as possible.”

And while very hot water can help to get rid of germs, our hands are unable to cope with the kind of temperatures needed to kill bacteria and viruses with heat alone. However, for dishes, the combination of heat and detergent will make cleaning them a lot more efficient, while leaving them to soak beforehand can also make a big difference rather than trying to blast off any stubborn food with running water.

For those looking to wash something larger than a cup or plate, avoiding running water is also generally a good rule. Using a bucket to wash the car rather than a hose can save a lot of water, energy and carbon. But one study found that using a bucket and sponge to wash a car, and then rinsing with a power washer was the most water-efficient method, using less than half as much water compared to a hose.

Lowering the temperature of the wash, combined with air-drying, could make a big difference to cleaning up your laundry-related carbon emissions

As for laundry, the most carbon-intensive part of dealing with our dirty clothes is drying them off, due to electricity-gobbling tumble dryers. According to one estimate, drying makes up about 5.8% of residential-sector CO2 emissions in the US. Heating the water for laundry accounts for a further 1.59%, while the actual washing itself makes up 0.9%.

Lowering the temperature of the wash, combined with air-drying, could make a big difference to cleaning up your laundry-related carbon emissions. As this also uses less electricity, it could also save you money.

“Cold-water use seems to be the transformation that people can make with the least effort,” according to researchers at Arizona State University who examined the carbon footprint of domestic laundry. For instance, a load of laundry washed at 60C, then dried in a washer-dryer, produces the equivalent of 3.3kg of CO2, compared to just 0.6kg for the same load washed at 30C and dried on a clothesline.

One analysis by the Sustainability Consortium estimated that if one load of laundry a week was washed on a cold cycle rather than warm or hot, each household could reduce its carbon footprint by 23kg a year. Given 26 million tonnes of CO2 are emitted in the US each year from washing clothes, it could go a long way towards reducing this.

While not everyone can be as fortunate as Lambert, who can hang her duvet cover outside in the Italian sunshine and have it dry within an hour, air-drying is feasible for many. After all, it’s common in damp Britain, and even people in humid climates frequently air-dry. One obstacle in the US, where tumble dryers are ubiquitous, is the prohibition by some homeowners’ associations of hanging laundry outside, because it’s considered unsightly. If you do have to use a dryer, using the high-speed spin cycle on your washing machine can reduce the energy needed as there’s less water to evaporate from your clothing.

Another option is to switch to a more efficient front-loading washing machine, which uses less water and energy, and is smaller, than a top-loading washing machine. The majority of washing machines in US are top-loading, creating a significant opportunity for change. According to one estimate, replacing 25% of US top-loading machines with front-loading ones could reduce electricity consumption and CO2 emissions by 5% on average.

When it comes to washing ourselves, it is obviously important to maintain good hygiene, but replacing a daily bath with a three-minute shower could save approximately 849kg CO2 per year, for a family of four.

Some showers are also less resource-intensive – mixer showers, which combine hot and cold water before the water emerges from the shower head, produce 100kg less CO2 over the course of a year than an electric shower. Installing shower heads that use less water can also reduce the carbon footprint produced by pumping the water to your home and disposing of it once it goes down the drain.

“A low-flow shower is not an oxymoron,” says Judith Thornton, a low carbon manager at Aberystwyth University in Wales. “You can get shower heads that simply spread the water around in a more efficient way. So you feel like you get just as wet, but you’re only using about seven litres a minute instead of 15.”

To give another example, shaving your legs in a wash basin rather than during a shower might use eight litres of water rather than 48, Thornton says.

In some cases the more convenient option is actually the lower-carbon one. “We’re all washing our hands for longer now,” says Thornton, noting the advice that has been issued about handwashing following the outbreak of coronavirus around the world. “You know how it is when you turn the hot water tap on, and it’s not until you’ve finished washing your hands that the water’s got hot?” If homes have narrower pipes between tanks and basins, or if pipes are better insulated, the amount of waiting time to achieve hot water can be reduced – making for energy efficiency gains as well as a better user experience.

Of course, we don’t necessarily need hot water to clean our hands properly. The mechanical action and the soap itself is responsible for cleaning our hands more than the temperature of the water. In order to kill the Covid-19 coronavirus with hot water alone, for example, it would require water temperatures above 56C (132F), which are hot enough to scald.

Washing our hands with a cooler, more comfortable water temperature, along with soap and a bit of elbow grease, could end up being kinder to the climate and just as hygienic.

Overall, individual water-use decisions can’t be one-size-fits-all. “It’s this funny blend of science, morality, public investment, commercial provision, the economy and working hours,” says Shove of people’s very diverse washing habits.

Thornton agrees, arguing that it’s necessary to understand why people wash the way they do, for instance, to get at how they might conserve water while also not breaching their fundamental right to water. People have different motivations for how they shower. An office worker who uses a shower to mark the start of her day, for example, might want to find another ritual such as brewing tea to get going in the morning. (Read more about the peculiar bathroom habits of Westerners.)

Governments can move things along too. For instance, encouraging the use of water meters and water efficiency labels on appliances can help people make better decisions. According to the water research and advocacy group Waterwise, if UK building regulations adopted a mandatory water label associated with a target of 85 litres per day, this would cut CO2 emissions by 55.9 million tonnes over 25 years. This would be equivalent to taking nearly a million cars off the road each year during that period.

But the good news is that some of the most impactful changes will come from tweaks to our daily habits. “The CO2 cost of water is 80% what we do with it in our homes,” says Thornton.

Just a few small changes to the way we wash could make a big difference.

How our daily travel harms the planet

Private transport is one of the world’s biggest sources of greenhouse gases, with emissions rising every year. In our car dominated cities, can we cut down the carbon footprint of our daily commute?

For many people, the journey to and from work are the bookends of the daily grind. But how we choose to travel to the office, or even to pop to the shops, is also one of the biggest day-to-day climate decisions we face.

In countries like the UK and the US, the transport sector is now responsible for emitting more greenhouse gases than any other, including electricity production and agriculture. Globally, transport accounts for around a quarter of CO2 emissions.

And much of the world’s transport networks still remain focused around the car. Road vehicles – cars, trucks, buses and motorbikes – account for nearly three quarters of the greenhouse gas emissions that come from transport.

So, the way you get around each day can make a big difference to your own carbon footprint.

You might also like:

● Should you go on a “flight diet”?

● Why your bin is a climate problem

● The surprising cost of being online

If you use a car frequently, the first step to cutting down your emissions may well be to simply fully consider the alternatives available to you.

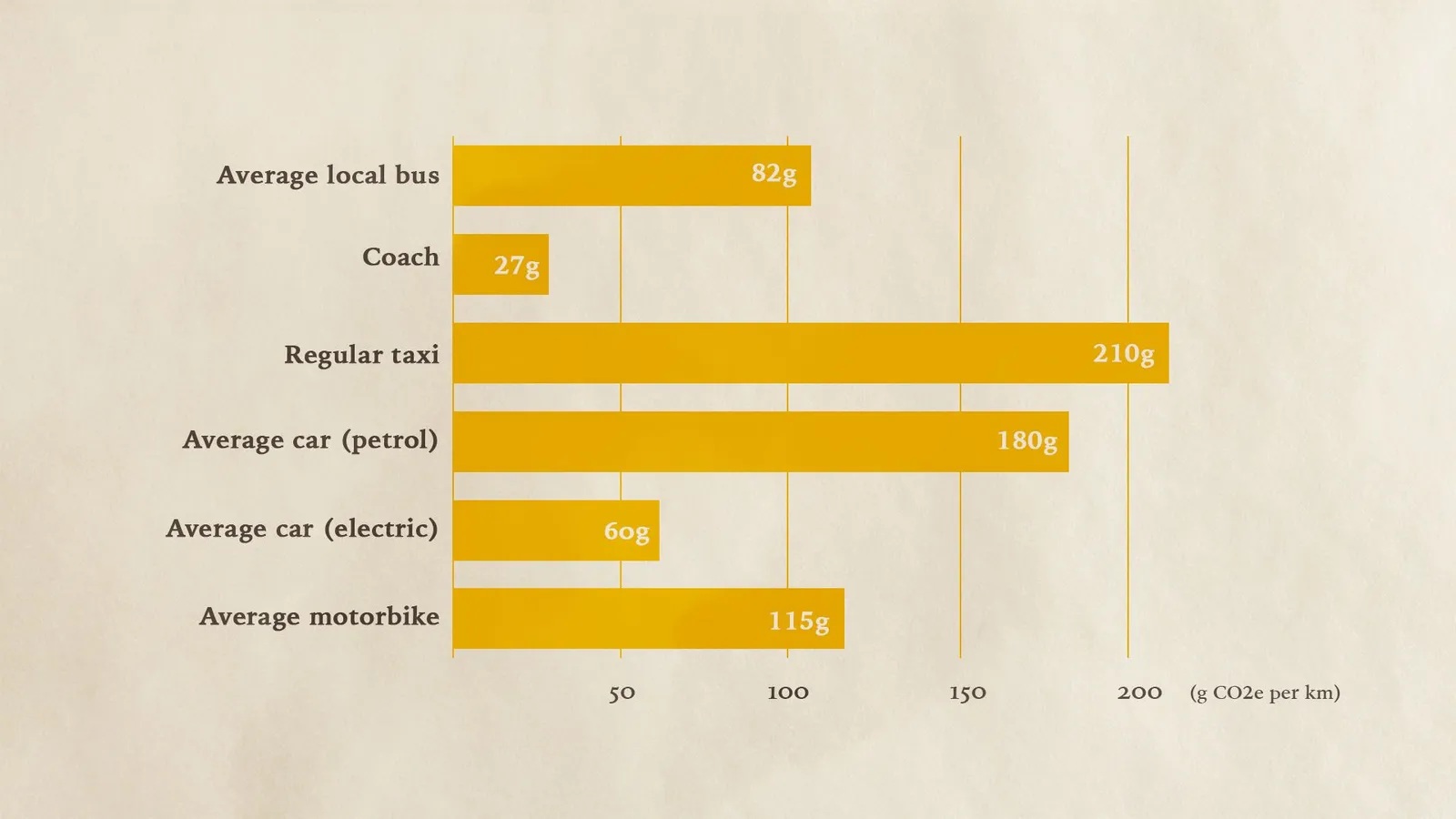

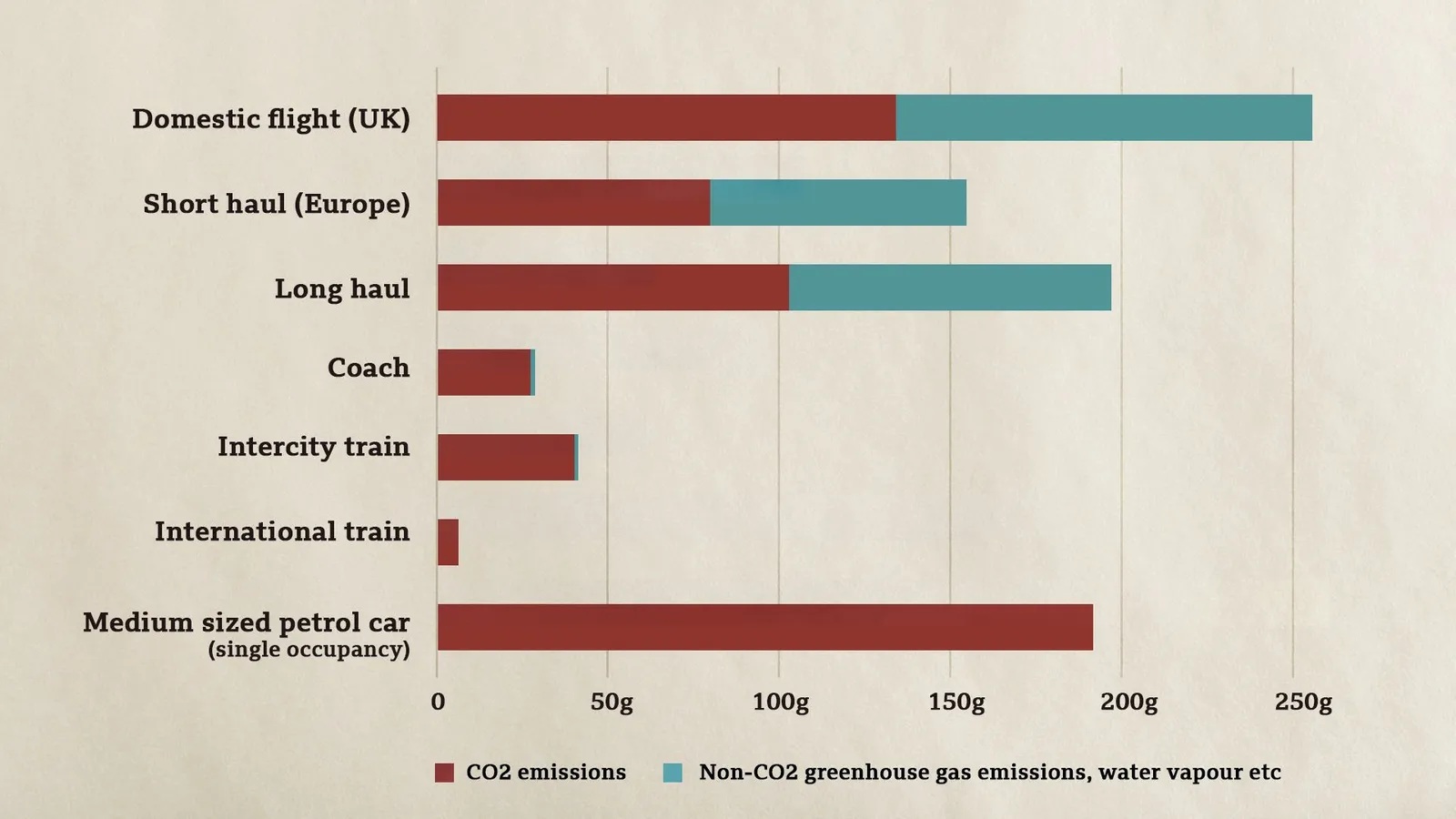

The average petrol car on the road in the UK produces the equivalent of 180g of CO2 every kilometre, while a diesel car produces 173g of CO2/km. In the US the average passenger vehicle on the road releases 650g of CO2/km. Generally, the larger the car, the higher the emissions.

Driving a newer vehicle can reduce these emissions – in Europe the average emissions for a new petrol car in 2018 was 123g of CO2/km.

But in many cases it may be possible to avoid using the car altogether. In many countries, even short journeys which could often be made on foot or by bike are usually made by car. In England, for instance, around 60% of 1-2 mile trips are made by car.

“From our perspective, the really low hanging fruit is the journeys that people could walk,” says Stephen Edwards, head of policy and communications at Living Streets, a British charity that promotes walking. “There’s an immediate contribution that we could all make to reducing our personal carbon emissions by walking more of those short journeys, whether it be to school, to the shops, to work or to the station.”

People often face psychological barriers to walking, says Edwards, and Living Streets aims to support people as they try to change their behaviour. During National Walking Month in May, it encourages people to substitute just one short car journey a day for a walk, and to experiment with incorporating walking into their daily routine.

Electric bikes and networks of segregated cycle lanes are beginning to change what is possible in terms of commuting distance

“I think once people start making that change, then it becomes sustained over time and the majority keep it up after May,” says Edwards.

Reducing car use on the school run is another focus for Living Streets. A generation ago, 70% of British children walked to school, but now less than half do, despite studies showing children who walk or bike to school tend to be more focused and are less likely to be overweight. Fewer cars around the school gate also means less local air pollution.

Dom Jacques, a parent of two from Leeds, in the UK, decided to do something when he became frustrated at the amount of congestion at the gates of his children’s school. Concerned about the potential impacts of air pollution and chaotic traffic on small children, he set up a local group to advocate for fellow parents to avoid driving their cars up to the school, and convinced the school to become involved with the Living Streets walk to school programme.

“The children were being educated about the benefits of walking on a daily basis,” he says. “They log their journeys on a daily basis as part of the project, they get really involved in the process… Then you can track whether or not you’ve been successful. It gives you a real insight into what’s happening.”

Living Streets says walk to school rates have increased by 23% after five weeks in schools where its programme have been implemented, while car journeys have fallen by around 30%.

Cycling, which shares many of the climate benefits of walking, is increasingly a viable alternative to car journeys, too. Some countries have sped ahead in bike transport: in the Netherlands 26% of journeys are made by bike, followed by Denmark on 18% and 10% in Germany. All three countries had major policy changes in the 1970s and 1980s that led to a large increase in cycling, and all still continue to invest in cycling infrastructure.

Often people may discard cycling as a viable option for longer distance travel. But electric bikes and networks of segregated cycle lanes are beginning to change what is possible in terms of commuting distance, says Leo Murray, director of innovation at climate change charity Possible (formerly 10:10 Climate Action).

In Copenhagen’s Farum cycle superhighway, the average bike commute is now 15km (9 miles), largely thanks to electric bikes. A recent report from advocacy organisation Transport for Quality of Life argued evidence from Europe shows electric bikes can transform our cities and should be financially incentivised in places like the UK. “Journeys that you just wouldn’t have made by bike before, now are actually trivial to make by e-bike,” says Murray. “And they are faster because you never sit in a traffic jam. The same is true to an extent for electric scooters.”

Many people, though, view public transport as the most obvious way to reduce their transport emissions, and it is especially important in the most congested urban areas. “All the economics are points in favour of it,” says Claire Haigh, chief executive of British sustainable travel organisation Greener Journeys.

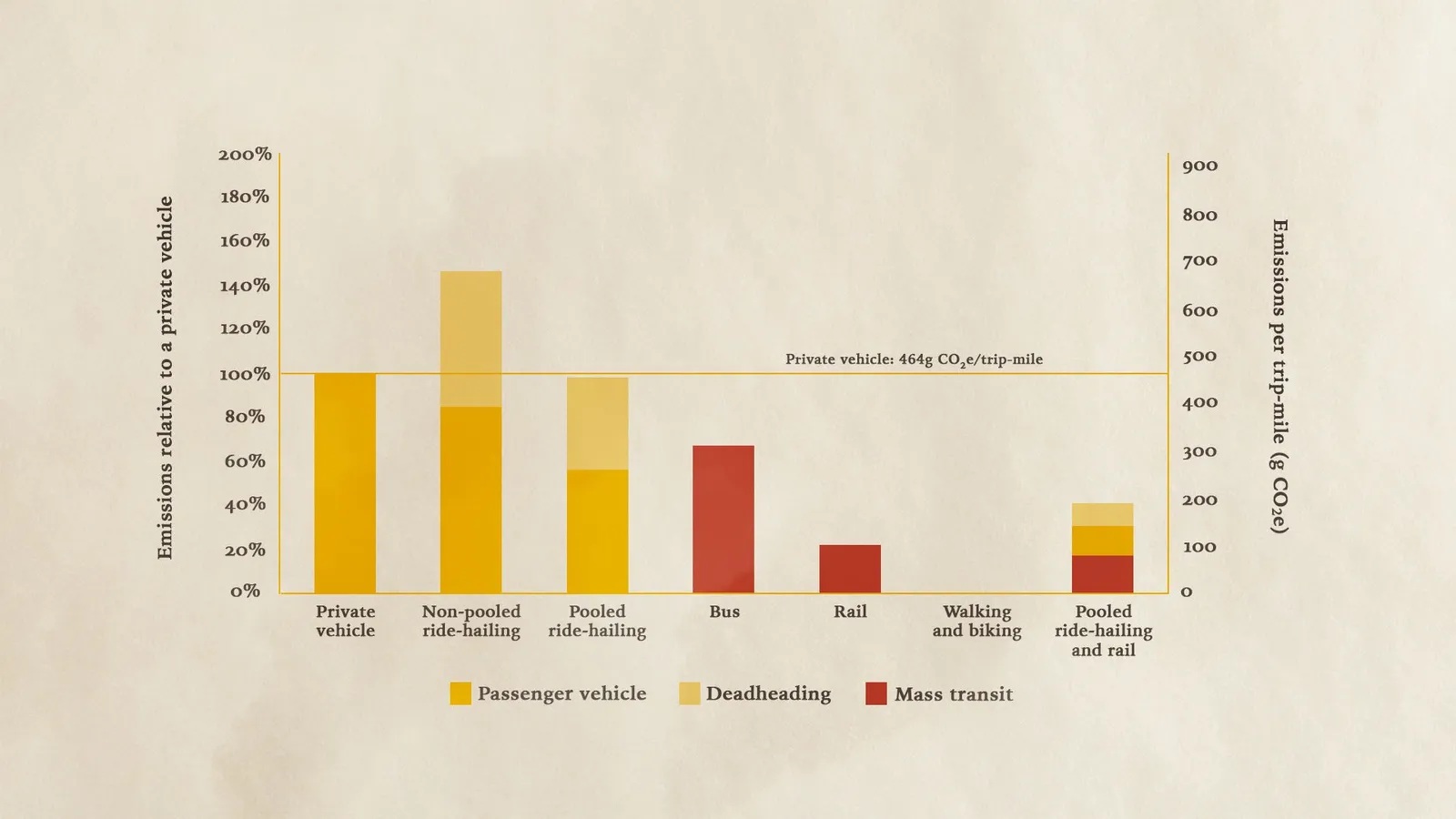

Travelling on light rail or the London Underground emits around a sixth of the equivalent car journey, according to UK government figures. A coach ride produces lower emissions still. Taking the local bus currently emits more, perhaps because the vehicles travel at lower speeds and pull over more often. But taking a local bus emits a little over half the greenhouse gases of a single occupancy car journey and also help to remove congestion from the roads. Bus emissions will go down further as more and more cities implement plans for electric and hydrogen buses.

Walking to and from the bus stop also gives people on average half their weekly recommended exercise, according to Greener Journeys research. “The great thing about public transport is it is also active,” says Haigh.

Taking a local bus emits a little over half the greenhouse gases of a single occupancy car journey and also help to remove congestion from the roads